Each year as we approach harvest time I am reminded of the shenanigans that go on around the production and sale of Extra Virgin Olive Oil. Let’s not forget that however important Nudo is to us producers and to you our customers, we are only a tiny wheel in the cog of a humongous international Olive Oil business.

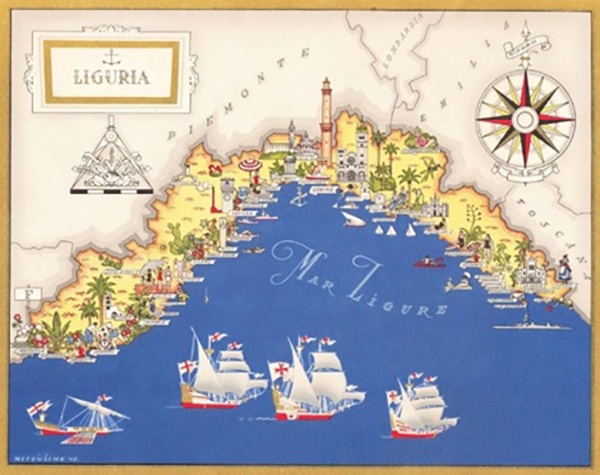

In my home town of Imperia, Liguria, every November, we celebrate the arrival of the Olio Nuovo with the annual Olive Festival when micro producers of Liguria’s best ‘prodotti tipici’ bring Imperia’s traffic to a standstill with stalls laden with food, plants and sometimes even livestock.

The local Taggiasca olive was introduced to the area by the Benedictines in the 12th Century but over the years this sweetest of olives has suffered something of a reputational damage due to the dodgy goings on of some of the larger producers and multi-nationals.

My friend Cathy Rogers, who founded Nudo with her husband Jason Gibb, jotted this down a few years back:

I make olive oil. I know every single step of the process inside out, from sapling to mature tree, from the plucking of the fruit to the winding of the press.

I also know how much all this labour of love costs. That’s part of my job too - watching every penny and dime we spend, but making sure we never cut corners.

So when I go into a supermarket and see a half litre/17 fl oz bottle of ‘Italian extra virgin olive oil’ for £3 ($6), I know that it can’t be true. Extremely unlikely that it is extra virgin, highly unfeasible that it is Italian and totally conceivable that it isn’t even olive oil!

Let’s look at the maths:

Each of our olive trees produces about two litres of olive oil a year. One year, one tree, one harvest, two litres.

Each tree costs about €5 to prune.

We cut the grass twice a year (sounds easy, but across 21 acres it becomes a little trickier) which works out as €2 per tree.

Then the other major expenses are the harvesting by hand, costing about €4 a tree, organic fertiliser at €1 a tree and using the communal press to squash the beauties, coming out at $1.5 for every litre.

So we are already up to around €7.50 a litre without including any of the farm overheads, taxes, marketing, organic certification, or big pasta lunches. We are however including the fact that we are paying decent living wages, we are not working people into the ground nor are we employing children.

But just considering the basic cost of product and we still need to add at least another €2.50 a litre for bottling, packaging and transport.

So we’re now up to €10 a litre.

With no profit taken by us a shop would typically want to sell this for €20 a litre.

This is a long way from our cheap, supermarket extra virgin olive oil. Sure there are economy of scale, and no doubt I could get the harvesters (who include myself incidentally), to work that bit faster, but it’s not going to reduce the costs by an order of magnitude is it?

Jason Gibb & Cathy Rogers and their daughter. Le Marche.

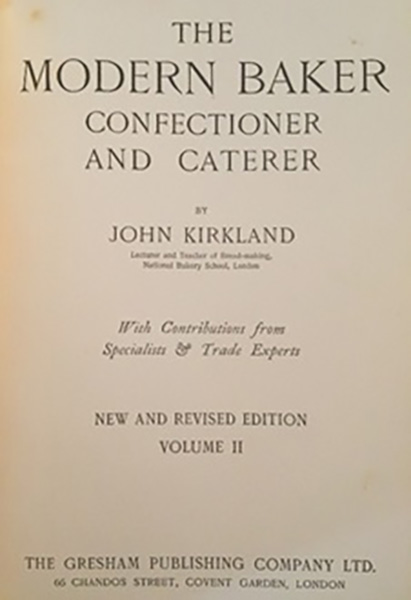

This is however by no means a modern phenomenon as I was amazed to discover when reading a copy of ‘The Modern Baker’ published in 1911. I love reading old cookery books but I am glad to say that our understanding and appreciation of olive oil has moved on somewhat since 1911!

Mr John Kirkland states:

‘The value of olive oil depends greatly upon its flavour and this varies with the locality in which the olives are grown. The rank, harsh taste of some of these oils disappears upon keeping sometime.’

(actually, no olive oil gets better with age)

and it goes on…

‘On account of its high dietetic value, olive oil is adulterated enormously, the commonest adulteration being cotton-seed oil, which is frequently entirely substituted for it. Other oils used for this purpose are sesame, rape, poppy archis and lard oils! The detection of certain of these substitutes is not particularly difficult when they are present in considerable quality, but the ingenuity of the adulterator is directed chiefly to the addition of a small quantity of a mixture of oils which have the effect of naturalizing each other so that detection of the fraud becomes a matter of great delicacy which can only be successfully undertaken by an expert oil chemist’.

Great Grandfather Daniel Smith and his daughter Flora outside the family bakery in about 1904.

The Modern Baker’ inherited from my Great Grandfather Baker Daniel Smith, 1863 -1933, of Gloucester

In recent years Italy’s micro producers - including our very own Nudo producers - have done much to try and rectify the image of not just the Taggiasca olive but the reputation of the olive business across Italy.

When we first arrived in Liguria I was given many warnings about all of the goings on especially the mixing of the local Taggiasca oil with imported oil from Spain or North Africa, but I was amazed at just how openly this is done and how widespread a practice it is.

Before our first harvest I read up and did a lot of research about what was happening in the newer territories for olive production such as California and New Zealand to see how people who were not hampered by years of tradition and the weight of supplying big business were operating.

In the end I decided to approach producing olives in the same way as I had seen people growing apples and plums in Gloucestershire as a child. My approach is that if a fruit, and olives remember are fruits, has fallen off the tree before harvest than it is simply not worth milling. For this reason and unlike many other producers in this (and other) regions of Italy, we only put our nets out on the morning of the harvest around the particular part of the grove where we will be working and we pack them up again at night when the olives are picked.

But it is true to say here in Liguria, as I am sure happens across Italy, nets are left under the trees for months to collect ‘windfall’ olives. The windfall is gathered up and collected every few weeks for processing. To make extra virgin oil the olives need to be pressed within 24 hours not three weeks.

We put our nets out in the morning of the harvest and only mill olives picked lovingly by hand.

So it comes as no surprise then that 4 out of 5 bottles of Italian extra virgin olive oil sold in the UK, USA and China DON’T have inside what they say they have on the bottle.

Which begs the question, what do they have inside?

As in Grandfather Smith’s day there are in fact numerous shocking examples where this 'Italian extra virgin olive oil' turns out to be mixes of chemically extracted olive oils, cut with nut or sunflower oil or both and it’s likely provenance is Spain, North Africa or Turkey.

And I repeat, we are talking about 4 out of every 5 bottles here folks.

So the moral of the story is that you get what you pay for.

Don’t take your olive oil for granted. Ask questions about its origins. And heck, you can even go crazy and adopt your very own 100% Italian 100% olive 100% tree and then you will know 100% what’s in the can!